Mike Cockrill

Falling in Place

Mike Cockrill

Interview

Art critic Ellen Lubell first met and interviewed Mike Cockrill in 1984 for an article in The Village Voice. Though they knew each other professionally, they would not date and marry until six years later. Mike thought an interview with Ellen would be worthwhile as she has closely watched his artistic evolution over the subsequent decades.

August 2025

EL: You have employed many different styles of drawing and painting over the years. Why?

MC: My earliest exposure to art was in children’s books that my mother read to us. In a Mother Goose book, which I still have, there were different illustrators for the different stories. At five I was fascinated to notice that the style of drawing affected how I felt about the story. Some drawings were scary and some drawings were playful, and some were just matter of fact. I think this was my first realization that there is no one way to draw and that the style an artist uses has a critical effect on the viewer. The content doesn’t matter as much as the way it’s drawn. Is the drawing of the frog cute and whimsical or dark and eerie? It’s still a frog, but the way you draw it changes everything.

EL: I'd like to talk about two things: the formal qualities of your work as well as the narrative qualities. You have said that the evolution of the subject matter in your art is of great interest to you and I'd like to discuss that.

MC: Sometimes I wonder if my subject matter has actually evolved. A few years ago a young assistant observed that my early work was involved with “individual death,” as in the Kennedy assassination, and my later work was concerned with “mega-death.” It’s a long story, but the Cuban missile crisis hit me at a moment of childhood that had a profound effect on my psyche. The idea that everything in my world, including my first classroom crush, could be annihilated in a nuclear holocaust in 15 minutes, had a deep effect on me. I was in the 4th grade, in a Catholic school two miles from the CIA and six miles from the Pentagon.

So there is a darkness inside the suburban cheerfulness of much of my work. Though my paintings don’t seem so cheerful anymore, they are still pretty. Even hell should be aesthetically pleasing. At least in art. I’ve thought about this: the aesthetic of suffering. No matter how much an artist may want to convey the pain and suffering of humanity, it’s still an aesthetic exercise. Goya’s Third of May is a beautiful painting, and it’s about genocide.

EL: I’d like to know more about your suburban landscapes. In some earlier works, sunlit suburban houses formed the horizon line in the background of your paintings. If, say, girls are killing clowns in the foreground, you had suburban houses in the background with children playing archery on the lawn as if oblivious to what's going on. But now those houses are in the foreground and the landscapes are basically devoid of any kind of life, completely empty. The houses are totally inhospitable: no doors, no windows. How have you evolved from happy suburban houses in the sun to houses of darkness?

MC: Well, I was growing up in the American Suburban Dream and one day the nuns said we were all going to die, so we should just forget about the duck-and-cover drill for nuclear war and head to the church sanctuary and pray. I sensed a satisfaction in them that we children were all doomed. I got the feeling they thought we deserved it. My mother took me out of Catholic school after that year. I was losing it.

This was in Northern Virginia, McLean. As children we became aware that all around us were the fields where men from the North and South had met and slaughtered each other in the Civil War. In the woods near my house we found musket slugs in the ground.

Recently I was talking to a young woman at an art opening who told me she grew up six miles from Appomattox Court House in Virginia where Lee surrendered. She was twenty-five years old and said, “You know – there is blood in the ground everywhere.” I was astonished she said that. They still think about that there.

As a child I witnessed trees being bulldozed down and the earth shaped, followed by houses being built. It was fascinating. New houses with no grass, no trees and no people yet. It was a strange, mysterious landscape.

This early experience of watching houses grow out of the torn earth undergirds my work. Are the houses in my art rising or are they abandoned? Is this creation or destruction? Some of my houses have scorch marks on them from being burned by a torch I carefully use in my studio. Then I may repair them after I burn them.

EL: One thing I wanted to ask you about the houses in your landscapes, as long as we're talking about them, is have you lost faith in the suburbs? Are the new houses in your work some kind of commentary on the suburbs?

MC: I’m not really sure if my suburban paintings are about the suburbs in any literal way. Years ago one of my former dealers said to me, “I like your real estate houses.” That made a light bulb go off in my head. I had been copying the houses in vintage ads just to get the architecture right. But you could tell in the painting that the house was from an ad and was not a “real” house. That was an important observation. The places I am portraying are not real. They are a construct and in a large way a comment on the America I have experienced. America is an idea based in part on a myth. The American Dream is a real estate ad in a magazine that went out of business 50 years ago. How is it working out now?

EL: That brings up an evolution in the way you approach and treat the surfaces of your paintings. They used to have standard smooth surfaces and everything depicted was behind the picture plane, but these newer paintings exhibit several different kinds of surfaces from sort of drippy to what I would call distressed; more three-dimensional and in front of the picture plane. Do you want to talk about that?

MC: That's very important to notice. I think I got tired of the beautiful, pretty surfaces I could create and I felt I needed to do something to change it up. I started sticking things on the paintings. For example, about 10 years ago I was working on a large acrylic painting and I thought it needed something; I actually cut up the shirt I was wearing and glued it on. I wanted to disrupt the surface.

Soon I needed to go to the thrift store to buy more men’s shirts. I wanted the ones with stripes as well as checks and camo patterns. Freudian alert! He’s cutting apart his father, who began his career as a civilian at the Pentagon. Or am I cutting myself apart? I used to work in an office at Merrill Lynch, long ago when I first moved to New York.

Nevertheless, I began gluing on fabric collage elements. It made it harder for me to control the image. It was a kind of deskilling. I can draw anything. I needed to thwart that, to interrupt it, so that I didn't have total control. The process of adding collage, painting over it, pulling it off and rearranging it, became a whole new way of working. It created accidental juxtapositions in color and texture that I wouldn’t have thought of if I was only using paint and a brush.

EL: Do you enjoy using the dimensionality this new collage approach gives you? I notice you will cut out a little square of white painted paper or fabric and literally build the house like a model.

MC: I could paint the house onto the landscape but that's just not satisfying to me anymore. But to build one with strips of fabric and to put it all together like it's a model is reminiscent of something I enjoyed doing as a kid. Maybe this goes back to my love of making models as a young boy.

In my studio I often rip my paintings apart and reassemble them. The process of destroying something and then building it back is kind of like -- is this painting coming into being or is this painting falling apart? and I like that tension. And of course, this is in the news every day. Utter destruction. Buildings and whole cities being laid to waste. Not to mention the lives destroyed. These are very fraught and horrific times.

EL: Let's talk about one of your newest series, which I call “The Covers,” because you're basically reinterpreting iconic paintings from bygone centuries and styles; there are several of them in this show. Those paintings have some of the most interesting and distressed surfaces on view. Can you talk a little bit about those?

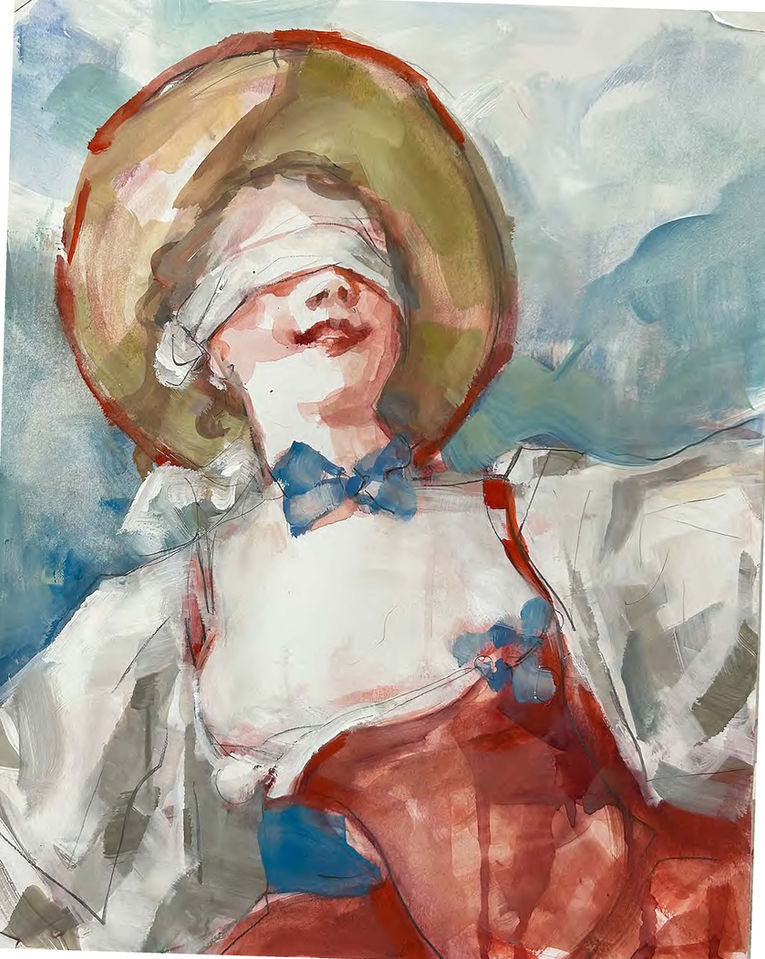

MC: Yes. I spent a lot of time copying great drawings by artists like Ingres and Degas when I was an art student. I avoided Fragonard. I did copy Watteau, but the Rococo bothered me. It seemed frivolous and silly. Ironically, that’s the period I'm interested in now. There's something about these doll-like women in billowing satin dresses playing blind-man's-bluff with these foppish men that is apt for our time. These Rococo paintings were made for the powdered-wig classes who were living in a kind of blindfolded delusion; their privileged lives are going to be toppled, their world is going to fall apart and they're going to be guillotined. Are they aware of that?

This could be a very apt metaphor for the moment we’re living in now, between the Have-Everythings vs. the Living-on-the-Edge day-to-day masses. The mega-wealthy fancy that they can just leave it all behind and fly to Mars. How is this going to end? Who is wearing the blindfold?

EL: Along with houses and covers of other paintings, you have also created a series of deconstructed men and fighter jets, all painted in a predominately grey palette. Please discuss.

MC: Those are my grey men. The paintings began as a series of soldiers and evolved into anonymous businessmen in striped shirts. The jets, men, houses and Fragonard covers are all made from the same torn and scavenged fragments in my studio. One painting will be pulled apart and reassembled into a man and then pulled apart and reassembled as a jet or a ravaged Fragonard or Watteau. Past is linked with future. Creation is linked to destruction. The world is in flux. Unstable. “Things fall apart; the center cannot hold. Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,” as Yeats said. How much chaos and fragmentation can we absorb? I’m an artist. I’m just reporting.

EL: Do you think your work is prophetic?

MC: (after a pause). I don’t know. People have told me it is prophetic, but I know why they think that. Because I’m painting the future when I paint the past. What have we ever learned? The future can’t escape the past. You paint some sort of nightmare you experienced or witnessed or learned of, and then a few years go by and here comes the nightmare again – and people say, “Oh, you saw that coming.”

I love life and beauty. I cherish them. These things are a blessing. Maybe that is what my work is about. The tension. The tension between life and beauty and The Nightmare.

Ellen Lubell is an art critic and writer who has written for major art publications and newspapers, including Art in America, The Village Voice, The Star-Ledger of Newark, and wrote about television for New York Newsday. In the mid-1970s, she founded womanart, a feminist art magazine; she was awarded a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship as that magazine’s editor.

Mike Cockrill has been making conceptually engaged, socially challenging work since he began showing in Brooklyn and the East Village in the early 1980s. Cockrill grew up in the Washington, DC suburbs during the Cold War-era with parents who worked for the Pentagon and CIA. He has a particular affinity for the pop-culture images of postwar America and their darker subtexts. He lives and works in Brooklyn.

Showing by appointment

49-28 31st Place, Long Island City, NY 11101

T: 888.MOSAIC2

About Mosaic Artspace

Mosaic ArtSpace (MAS) is a multi-discipline art venue that aspires to showcase and promote various artistic endeavors with outreach to painters, sculptors, musicians, video, performance, installation artists.

MAS hosts the artwork of local artists and artists from the NY Metropolitan area and other cities.

MAS seeks to create a dialogue with issues of contemporary art practices to encourage, support and expand creativity and self-expression. To create an environment in which the arts flourish and enrich the quality of life.

Contact

© 2022 MOSAIC artspace